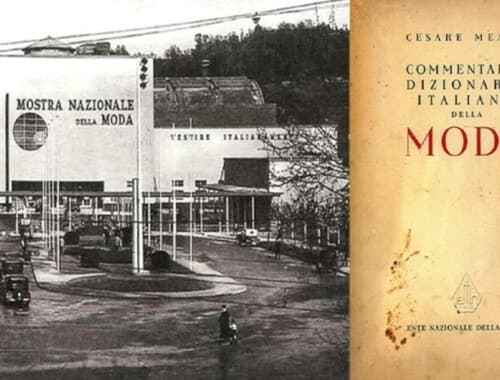

ENTE NAZIONALE DELLA MODA

E , FASHION PLACES , ORGANIZATIONS

ENTE NAZIONALE DELLA MODA

In 1935, at the end of October, the fascist regime launched the Ente Nazionale Della Moda which had the task of Italianizing the women’s wardrobe and adapting it to the commandments of autarchy.

The war in Ethiopia had just been unleashed. Mussolini, from the fatal balcony, had said: ‘We have been patient for forty years, that’s enough and the troops of the quadrumvir Emilio De Bono boldly sprinted to free Adua, Axum, Macallé: a boldness that, a little later, was often frustrated by the resistance of the Ethiopians.

In Geneva, the League of Nations, the first and most irresolute edition of the UN, declared Italy an ‘aggressor state’, issuing economic sanctions and an embargo for certain products. Rome had responded by launching the ideology of ‘we are enough for ourselves, of autarchy.

THE IDEA OF “CONSUMING ITALY”

The Italian people had to ‘consume Italy’ and happily wear casein wool, animal, and cotton made from broom fibers. Independence textiles came into production and even fashion had to become independent from the diktats of Paris, it had to be Italianized like certain words borrowed from English and French: “amoretto” instead of flirt, “arzente” instead of cognac.

It was up to the tailors to create national elegance. They were not enthusiastic about this. Also, Mussolini was exacerbating the situation, and before the sanctions that had forced Italy to do it on its own.

The Duce, from a podium in the background of the Milanese Castello Sforzesco in May 1930, had proclaimed: “An Italian fashion for furniture, decorations and clothes still doesn’t exist: it’s possible to create it and we have to create it”.

So the “gatherings of fashion were organized”. In April 1933, Turin elected the capital of elegance, organized exhibitions and fashion shows in the name of Italian style and Mussolini telegraphed: “If the beginning is good, what follows will be better: we must have faith”. Faith was also stimulated by decrees from above.

THE IDEAL OF A WOMAN

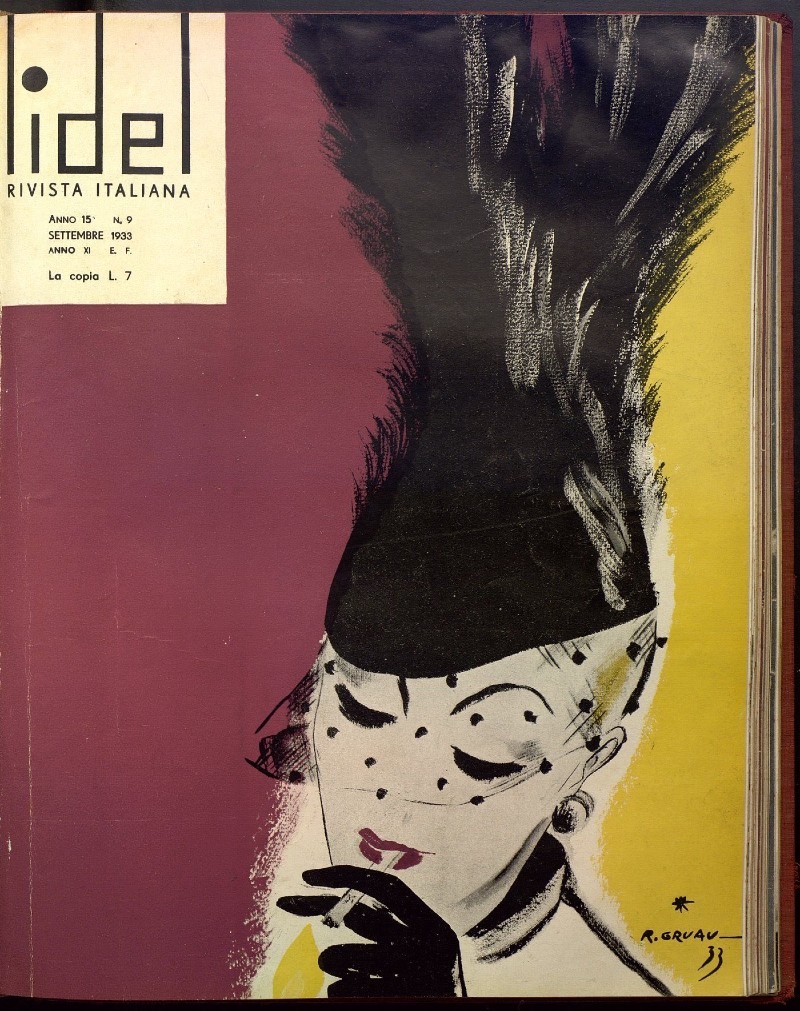

Lidel, one of the most enthusiastically aligned magazines of local fashion, advised “slenderness, not thinness” and represented figures with robust arms, pronounced hips, and round breasts. The endocrinologist scientist Nicola Pende dictated the perfect measurements of the models to the Fashion Agency: 1.56/1.60 in height, 55/60 kilos.

September 1933

September 1933

According to the will of the Duce, it was necessary to give national clothes to the healthy miraculous woman with a “soft grace that she had been proud of for many years, but that for about ten years she had decided to deny”. But tailors and seamstresses were a niche because the customers demanded Paris fashion or something similar at least. Only Marta Palmer and the Lamma tailor’s shop in Bologna strictly followed the directives, even banning the ritual travels to Paris twice a year. At that time, the Fashion Agency invented the hallmark to be assigned only to ‘Italian design and production models.

THE RULES IMPOSED BY THE NATIONAL BODY OF ITALIAN FASHION

In a collection, at least 50 percent of the clothes had to be able to exhibit the certificate of Italianness, under penalty of a fine of between 500 and 2,000 lire. Often the houses, having obtained the mark of virginity, hid it from customers because, if not, the models remained to age in the wardrobes, unsold. The lie could cost between 1,000 and 5,000 lire in fines (a huge amount of money in the times that sang ‘if I could have a thousand lire a month’), but saving a collection was worth the risk.

The craving for elegance and the conditioned reflection that chic could only be Parisian seemed, therefore, invulnerable to the decrees, to the proclamations of Mussolini who, in the years of autarchy, of “proletarian Italy standing”, of the empire on the “fatal hills of Rome” was at the top of the consensus.

In 1937 the magazine Per Voi signora, cited by Natalia Aspesi in her important and detailed volume Il Lusso & l’autarchia (Rizzoli, 1982), had all the reasons to be outraged: “After fifteen years of fascism, after two years of activity of the National Fashion Agency, when the memory of nine months of sanctions is still alive, some Italian tailors base their collection exclusively on Parisian models and consider that part of the collection itself equipped with the brand of the institution as a negligible fraction, artistically inferior, such as not to characterize the whole of their production at all and on which in any case it is good to keep the most absolute silence.

THE COLLECTION

The real collection consists of French models. It was not the stubbornness of the insiders, nor was it a form of docility towards the regime. Significantly, tailors and seamstresses had to look after their customers. Notably, La Gazzetta del Popolo underlined, “showed that the customers accepted the Italian dress with personal sacrifice and endured it as if they had to bear a habit out of a pure spirit of discipline. While all their dreams of exotic elegance broke there, on the border, against those tightly closed doors”.

Some seeds, however, took root. On the catwalks of Villa d’Este (fashion show commissioned in the spring of ’38 by Mario Allamel who directed Rhodiaceta of the Montecatini Group, a manufacturer of artificial silk yarns and organized by Carlo Rossi); of Campione, the Mirafiori racecourse and in the ateliers in Milan, Turin, Rome, Ventura, Battilocchi, Ferrario, Gori, Gandini, Zecca, Fercioni, Luigi Bigi; the debutant Biki, Vanna, Fumach-Medaglia, Biancalani, Rovescalli, Ayazzi-Fantecchi, Cerri and Tizzoni spread autonomous talent in order to “create and dress in Italian style”.

“They were cries” Biki recalled, “they were attempts that relied above all on the use of Italian fabrics, local trimmings, lace, and embroidery of our very high craftsmanship. Despite the efforts, there was a lack of competence and unity of purpose. Absence of real overall strategy, and it was easier to buy the paintings of the great French from Pedrini, who bought in Paris and sold in Italy, doing gold deals.”

Those cries did not charm those who could use the wallet with impunity. The aristocracy did not give up on Chanel, Molineux, Lanvin, Patou, Vionnet, Lelong, Schiaparelli. But there was an atmosphere of war: Paris was moving away and a little later, with Nazism, it became a monopoly for the purchase of Eva Braun’s little sisters, wives, companions, girlfriends, and friends of the Third Reich.

THE “CLOTHING AND AUTARCHY” CONGRESS

That seemed to be the right moment for the Ente Moda for the definitive effort “given the new tasks that Italy will certainly have to fulfill in the field of fashion, in a new European order that will be created by the Axis powers”. On the eve of the conflict, there was a congress on “clothing and autarky”.

Italy was taking its first bitter blows in Africa. During then, the Ente Moda triumphantly disclosed that it had issued almost 14,000 warranty licenses and was thinking of a gold mark for the most patriotic, more national clothes. The country grew thick with war widows, mothers of heroes, and girlfriends of the fallen.

THE FORTIES ACCORDING TO THE ENTE NAZIONALE DELLA MODA ITALIANA

Made in Italy fashion was experiencing positive months. It seemed close at hand, as L’Illustrazione Italiana wrote. After the grand parade of autarchic fashion in Venice in the spring of 1941, the goal was to “oblige capricious ladies. This was said with both respects and listened to with patience. To achieve following the fashion of our home.

Our fabrics, our models, our packaging, an exclusive fashion that we will be able to export. Mainly, because it bears the indelible mark of Italian commitment and imagination. All overseas and beyond the mountains foreign horizons have opened up to clothing”. They were dark horizons of tragedy and darkened even more.

But the Ente Moda continued to distribute its gold brands. To Biki for a three-piece that allied silk crepe, linen, and wool, to the Ayazzi-Fantecchi and Ciottoli milliners. Who, in the setting of the municipal theatre of Florence, was framed by a beauty photographer. He had embellished the hairstyles of Mita Pandolfini, Simonetta Corsini, and Paola Antinori.

The strong hope in a very Italian fashion was not buried by bombs. But basically, hope remained, with some hint of reality. Precarious realities because, as soon as peace rose, it was realized that the psychological subjection to Paris was great. The need for the dernier cri, hammered and re-hammered even in the conventions of language. Although it had never died, it was alive, well, and ready to clear the way to the French monopoly, to foster wardrobes until the advent of ready-to-wear fashion.

ENTE NAZIONALE DELLA MODA ITALIANA. THE AUTARKY

But those decrees, those order sheets, perhaps, plowed the ground, educated to the idea that you could try a fashionable Italian way. The journalist Elisa Massai said: “Autarchy had at least the merit of forcing the fashion houses to leave at least a little bit behind. The very comfortable habit of buying in Paris, multiplying in Italy, and selling.

It ended up that everyone bought the same things. Yes, there were two, or three designers who used Paris and recreated, Pascali, Pelizzoni, and Elio Costanzi. But no one would have had the idea to give a damn about the great French. Otherwise goodbye customers.

Casa Ventura was even flaunting a Paris premiere, born and raised in one of those legendary ateliers and captured in the 1930s. Beyond the forcing, the nationalist idea of an Italian fashion was by no means busted. Our craftsmanship was top-notch. We had precious hands in the tailors.

Our men’s tailors were among the best in the world. Often the fabrics, which seemed English, only had the English label. They were our products, except for some cashmere products that we only started working on in the 1950s.

Il project of a fashion of our own, a style that did not pay tribute to France, was not far-fetched. There was fertile ground, a favorable hinterland. This was proved by the first Florentine fashion show in February 1951, our ready-to-wear fashion. During the period of the autarchy of the war, something moved: models that were somewhat copied but with something new inside

Read also:

ENTE MODA ITALIA

September 1933

September 1933