Albini, Walter

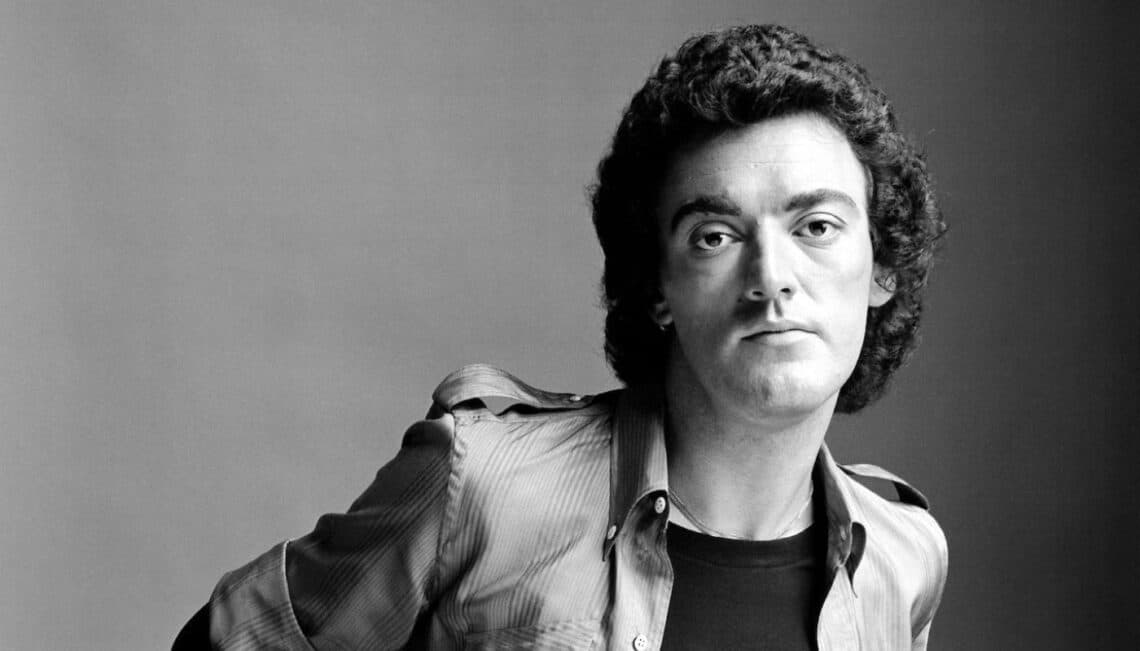

Walter Albini (1941 – 1983) was an Italian fashion designer. His name is without doubt among the most evocative ones in Italian fashion, even if his specific contribution is barely known outside textbooks about the history of fashion. And fashion itself, more inclined to mythologizing than to theorizing, hesitates about the evanescence of this extraordinary figure, leaving it in a suspended dimension, even if there are recurring tributes.

The beginning and the work with Krizia and Karl Lagerfeld

He was born Gualtiero Angelo Albini in Busto Arsizio (Lombardy) on 3rd March 1941. Against the advice of his parents, he left classical studies to attend, as sole male student, the Institute of Art, Design and Fashion in Turin. At 17 he began to work with magazines and newspapers, making sketches of the fashion shows, first in Rome, and then in Paris, where he moved for four years (from 1961 to 1965). There, he met Coco Chanel, falling under her spell. Not by chance, indeed, he took over from the seamstress Noberasco the complete years of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Le Jardin des Modes from 1918 to 1944, which in his opinion was the most creative period of Coco.

After meeting Mariuccia Mandelli, alias Krizia, in Paris, he worked three years for her and, in the last season, he also worked with Karl Lagerfeld, who was just starting out. In 1963 he designed his first collection and in 1969 he took part to Ideacomo, the manifestation where he presented the textile production for the following Summer. In the same year he proposed to Montedoro the uni-max formula, characterized by the same cuts and colors for menswear and womenswear, and the famous Anagrafe collection: eight brides wearing pink long dresses and wight widows wearing black short dresses. At the time he was the most famous Italian fashion designer and everyone in Europe competed to have him; but he also was very intolerant to every limitation.

Walter Albini treads catwalks in Milan

The FTM Group took up the distribution of his collections, designed with common elements in a single style for five separate fashion houses, each specialized in a different product (jackets, knitwear, jersey, dresses, shirts): Basile, Escargots, Callaghan, Misterfox, and Diamant’s (replaced by Sportfox few months later). In this way he obtained a complete line, which he presented in Milan instead of Florence, which at that time was the customary place to show a collection; he took the space and the time he needed. Others fashion designers left Florence, such as Caumont, Ken Scott, Krizia, Missoni and Trell. It was the beginning of Italian prêt-à-porter. But, while the international press called him “the new Italian star,” “as charismatic as Yves Saint Laurent“, the Italian one proved to be myopic and provincial, as did the distribution system. Albini, disheartened, broke all his contracts but the one: he continued his partnership with Misterfox, which produced with a new menswear and womenswear line which carried his name and was presented for the Spring-Summer 1973 season in London.

It was the first appearance of a new formula, later much imitated: a primary line with a strong and driving image, and a limited volume of sales, was economically supported by a second and more simple collection, aimed at a larger market. Albini, who lived (and designed) like a character by Scott Fitzgerald, called it The Great Gatsby. In this moment he created the unstructured jacket, the shirt-jacket (sometimes made of the same fabric as the shirt worn below), which was to be so important for the future of fashion in Italy.

In 1973 Walter Albini opened a showroom in via Pietro Cossa in Milan and bought a house in Venice. There, at the Café Florian, he mounted a memorable show, presenting clothes which seemed to come out of a timeless dream. The show was later brought to New York. His extraordinary creative talent was by now recognized all over the world and he was able to give shape to his own personal dreams as well as to ideas found in the broader culture, always with a light touch. And, yet, Albini didn’t receive enough support, he didn’t have a solid commercial organization behind him.

The ’70s

The crisis arrived in 1974-1975, though his collections continued to amaze for the particular beauty of his creations, with their refined fabrics printed in patterns such as the paisley. In this way he relaunched the Kashmir-inspired prints which moved from fashion to home furnishings, with a success that lasted many seasons and continues still today. Among other famous patterns created by him, besides stars, stripes, and dots, there were faces, dancers, Scottish terriers, zodiac, Madonnas, a houndstooth design, and giant Prince of Wales printed on silk and on velvet. Creator of the total look, he embodied it first of all in a completely personal way, by identifying his way of life with his creative style, then by furnishing his houses to match his fashions and designing in similar style fabrics, objects, furniture, glassware and coordinated interiors for design magazines such as Casa Vogue.

He was an excellent draftsman and, when he skipped a season, as in Autumn-Winter 1974-1975, he proposed, in a moment of reflection and as an alternative to collections, an exhibition of his sketches dating from 1962 on. He travelled a lot, especially to India, the Far-East and Tunisia, where he bought a house in Sidi-bou-Saïd.

In 1975 he presented his first solo menswear collection, anticipating again the future. In January 1975, in Rome, his first high fashion runway, in partnership with Giuseppe Della Schiava, who manufactured the printed silks to one of his drawings, took place. The collection was inspired by Chanel and the 1930s world. “It has never been a mystery that the ’30s are, in my opinion, a crucial moment, without nostalgia”. His second collection was entirely pink-colored, still inspired by Chanel, but also by another famous French couturier, antagonistic to Coco, Paul Poiret.

The collections by Walter Albini

From time to time, his menswear collections were presented by male friends (and by female ones, to emphasize the unisex concept), on busts that narcissistically reproduced his own image, through life-size photographic portraits of himself made by his photographer friends, or on panels carrying a mask reproducing his face. Sometimes, polemically, they were reduced to a grouping of robes trouvées, as if to state that what really counted was only the ars combinatoria. Once he dreamed up a scandalous exhibition of personalized phalluses dressed as a devil, Mickey Mouse, and Lawrence of Arabia, and also as Lagerfeld, Fabio Bellotti, and Saint Laurent.

Ever recurrent motifs in his fashion were the style of the ’30s, half-belt jackets, flat necks, large trousers, shirt-jackets, sandals, two-toned shoes, Bermuda shorts, and later on sleeveless jackets, knitwear caps pulled down over the eyes, and the first heavy-duty boots. In his last years he worked with Helyette, Lanerossi and Peprose. He entrusted collections bearing his own name to Marzo, a new company, but the manufacturers didn’t keep their promises. Paolo Rinaldi, his most faithful working partner and press agent, was always at his side. In the early ’80s, the press, always concerned with new entries, ignored him.

On 31th May 1983, Albini died at the young age of 42, leaving behind an unforgettable lesson in style, to be studied again only after his death, in the light of his great achievement, nourishing his myth.

A revolutionary designer

His revolution was the creation of notable clothes which weren’t anymore in limited edition, but whose price was lower and accessible to everyone: they were conceived above all for the middle class, for everybody who couldn’t afford a tailor’s shop. Brilliant, refined, rigorous, superstitious, passionate into astrology (he was a Pisces), Walter Albini gave a vigorous push to Italian prêt-à-porter as an expression of design applied to fashion in an innovative way, but with solid historical roots. He invented the new image of a woman wearing jackets, trousers or shirtdresses. He the revival as an intelligent way of research and reinvention, and he used irony and dissent as a means of criticism. He affirmed the total look, paying great attention to accessories and details, which to him were even more important than the dress itself, while adopting a maniacal perfectionism that was somehow detached and natural.

Fragile in his need of love, but perfect in his sketches, he worked without holding anything back, but never in haste or roughly or with mediocrity; he never accepted compromises, diminutions of style or restrictions imposed by the market: “Everyday I scold everybody a ugly truth: the fact that you anyhow try to kill dreams”.

You may also like:

To read the item in Italian click here.